THE HISTORY OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE AT HENNEPIN

Hennepin County Medical Center (HCMC) evolved from Minneapolis City Hospital (1887-1901), Minneapolis General Hospital (1901-1964), and Hennepin County General Hospital (1964-1974.)

In 1955, Professor Owen Wangensteen, Chair of the Department of Surgery at the University of Minnesota (UM), assigned one of his surgeons, Claude R. Hitchcock (1920-1994), to the Minneapolis General Hospital (MGH) to be Chief of the Department of Surgery. The “ER” was already run by a surgery department that consisted of academically inclined community surgeons who donated their time to teach and supervise. The ER was usually staffed by interns and one first year surgery resident. Hitchcock’s arrival enlivened the hospital with his energy and his love for teaching and research. Like his mentor, he was a stern administrator and believed that medicine was a 24/7 occupation. The hospital became well known for its surgical expertise, especially for trauma and cancer surgery.

In 1965, hospital and nursing administrations selected Hildred Prose, RN, an ER staff nurse since 1951, to become Director of Emergency Services, answering directly to Hitchcock. The ER had become very busy, overcrowded, and understaffed. She was a strong advocate for the ER patient. She became a thorn in the side of administration and that of Hitchcock with her admonitions about staffing and space needs. In the late sixties, the ER was remodeled and enlarged, expanding into space that had been the ambulance garage. Hitchcock also encouraged the ambulance service to train its “drivers” with basic emergency skills. Interns were no longer required to ride ambulances. Still, the ER remained overcrowded.

The sixties saw the advent of Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) that could be initiated pre-hospital. Ambulance personnel and fire fighters applied this new skill enthusiastically. Persons previously pronounced dead in the community were now rushed, CPR in progress, to the ER already teeming with patients. Although attempts were made to resuscitate them in ER cubicle space, monitoring equipment and other tools were lacking. Prose wrote long memos to Hitchcock about problems. He was already extremely busy leading his department in vital areas, such as renal transplantation and wound infection treatment with hyperbaric oxygenation. In 1971, Hitchcock called Ernest Ruiz, a general surgeon on his staff, to his office and asked him to “run the ER.” Ruiz was four years out of his surgery residency. He had experience in trauma surgery and knew that improvements could be made. After conferring with his wife about the consequences of this new assignment, they agreed that it was the right thing to do. He met with Hitchcock to accept the offer.

Ruiz specified that it was on condition that the ER was to be under his control without interference from Hitchcock or the other departments – it was to be an Emergency Department (ED) instead of an ER. Hitchcock nodded his approval. No papers were signed. Ruiz became Chief of the Emergency Department. He remained on the surgical staff and helped provide surgical coverage for fifteen more years.

Ruiz found that he had much to learn if he was going to be an emergency physician as well as a general surgeon. One never knew what was going to come through the door next. It was obvious that residency training in EM was needed. Two second year surgery residents, G. Patrick Lilja and Robert S. Long (1938-2005) were drawn to the ED by its variety and intensity. They had read an article in a news magazine describing the new residency in EM at Cincinnati General and called it to Ruiz’s attention. Within days Ruiz put together a curriculum and sent it off to the fledgling ACEP for a reaction. No response returned, but the residency was started anyway in the fall of 1971 with Lilja and Long as the first residents. Hitchcock allowed the two residents to switch to EM and even agreed to continue their stipends for the remainder of their year. The various services welcomed the additional support from EM residents. Hitchcock never told Ruiz he approved of EM, but his support for the residency showed his willingness to give it a chance.

In 1972, one of Ruiz’s first goals was to stop the practice of rushing critical patients “upstairs.” A well equipped room in the ED should be kept ready for such patients. Prose was in complete agreement, having observed the dangers of the rush-upstairs practice as an ED nursing director. An ENT exam room could be refurbished as a “Stabilization Room.” Prose successfully recruited a respected Night Supervisor who was expert in getting critical care initiated. Audrey Kuhne, RN (1929-2005) joined the ED nursing staff in 1973 and helped the Stabilization Room effort obtain hospital-wide credibility and support. Ruiz and Kuhne were successful scavengers of equipment and supplies from throughout the hospital. Some equipment was of their own design and made from scratch. The Stabilization Room contained the equipment necessary to resuscitate almost any kind of emergency patient to the point that he or she could be safely moved. Many innovations were introduced there. For example, cardiac ultrasound was first used there to diagnose cardiac tamponade on presentation to an ED. Not all cases could be “stabilized,” but IVs could be started, airways opened, x-rays and labs obtained, and life-saving measures taken while an operating room or intensive care area got ready. To our knowledge, the Stabilization Room was the first of its kind in the U.S. It can be stated that it started a new age in emergency care.

Lilja and Long graduated from the EM residency in 1972 and became EM staff. They almost immediately began a first-of-its-kind program of training pre-hospital personnel in emergency skills on their own initiative. This included HCMC ambulance “drivers,” police, and firefighters. The ambulance drivers became Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT) and Paramedics according to the skill level they achieved. ED nurses lamented that Lilja and Long were not always in the ED, but when patients arrived in better condition, they appreciated their efforts.

In 1973, Ruiz was in the ED when a call came from the airport reporting that an airliner was about to land without its landing gear. The runway was G. Patrick Lilja, MD 7:00 am being foamed. Ruiz and a resident grabbed emergency equipment bags and went to the airport in two ambulances. An ambulance from another hospital also went to the airport. The plane skidded in safely and all was well. Ruiz, however, was disturbed by the lack of coordination and communication between hospitals and rescue services made evident by the happenstance response to the near-disaster. At that time there was suspicion between hospitals that ambulances were out to steal patients. Some police and fire departments were ambivalent about training in emergency care.

Radio communication between all of the participants was unreliable. Ruiz called a meeting of police chiefs, fire chiefs, emergency department directors, ambulance services, hospital administrators, and Hennepin County administrators. All agreed that a coordinated emergency response system for all emergencies was needed. The group learned that a competition for a $400,000 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant was being offered to stimulate municipalities to improve emergency communications and training. Lilja and Long and others put together the grant request. It was awarded to Hennepin County with Lilja as primary investigator. It resulted in a state-of-the art communications system, paramedic training and certification, cardiac defibrillators for pre-hospital use and, ultimately, the West Metro EMS system.

Emergency Medical Services (EMS), created and nurtured under the careful leadership of Lilja and Long, has grown into one of the premier EMS systems in the U.S. Hennepin County is now served by five ambulance services staffed by career paramedics. Air medical services are now provided by LifeLink and North Aircare. Pat Lilja was a prime mover in establishing helicopter service in this area. He served as the EM Director at North Memorial Medical Center and Medical Director of North Aircare. In 1985, Brian Mahoney, HCMC EM staff physician, met with Ed Lord of the Veterans Administration to start the Twin Cities chapter of the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS). Annual drills involving 50 organizations from the East and West Metros are held. When Grand Forks, N.D. was flooded in 1997, NDMS evacuated patients from hospitals there to the Twin Cities using C130 aircraft. Mutual support also paid off when the 35W bridge fell into the Mississippi River in 2007. In a little over an hour all victims were cleared from the scene. EM staff physician, John Hick, is a respected spokesperson, teacher and hands-on leader in Minnesota’s Bioterrorism and Disaster Preparedness efforts. In the 70ʼs, HCMC surgeons and emergency physicians were leaders in establishing a regional trauma system. The Emergency Medical Services Advisory Council of the State Health Department identified trauma receiving hospitals throughout the state. They were designated Level 1, 2, or 3 Trauma Centers according to American College of Surgeons guidelines. In the 90ʼs, EMS placed Automatic External Defibrillators (AED) in the hands of first responder agencies. Many lives have been saved by fire fighters, police, and sheriffs who successfully defibrillated patients in cardiac arrest. Studies found that most of the high quality neurologic saves were in patients defibrillated early using an AED. Our Paramedics have been doing prehospital 12 lead electrocardiograms for years. They activate the cardiac catheterization lab from the field for ST elevation myocardial infarctions. HCMC Interventionalists have the best door-to-open-vessel time in the country. EMS education staff train over 2,000 EMTʼs and first responders a year. EMS has also conducted vital prehospital research including three National Institute of Health funded studies: Public Access Defibrillation; ResQ (enhanced CPR) Trial; and the 10 | Department of Emergency Medicine Activities Report | 2009-2010 Rapid Anti-seizure Medication Prior to Arrival Trial (RAMPART). Jeff Ho, an EM staff physician, has monitored TASER use by law enforcement in our area and offers scientifically sound recommendations for its use. Drs. Ho, Hick and Mahoney provide field supervision of HCMC ambulance paramedics.

HCMC, including the ED, is on the cutting edge of the digital documentation revolution. This has been possible in the ED because both nursing and physician staff have been led by leaders with computing skills. Marsha Zimmerman, RN, and Joseph Clinton, MD have patiently overcome the difficulties associated with this huge challenge. Other departments, especially Medical Imaging, have also contributed.

Acute Psychiatric Services (APS), formerly known as The Crisis Intervention Center (CIC), had its beginning in Minneapolis General Hospital in the 60’s when a telephone on the ER nurse’s desk was dedicated to “suicide calls.” In 1967 Zigfrids Stelmachers (1928-2006), a Ph.D. Psychologist in the Psychiatry Department, arranged for Mental Health Center staff to relieve ER nursing staff of this responsibility. In 1968 a small area adjacent to the ER was added to allow face-to-face interviews between mentally unstable or depressed patients presenting to the ER and clinical psychologists. This unit, under Stelmacher’s direction, was the first hospital based CIC in the country. In the 70’s, the role of the CIC was expanded to help in the evaluation and disposition of patients being held in “holding rooms” of the ED. Conversely, EM staff helped CIC staff evaluate medical problems. This cooperative arrangement continues between the ED and APS.

HCMC’s Poison Control Center (PCC) began in the middle 70’s when the numbers of calls about possible or real poisoning and drug reactions caused medical staff to be called away from patient care. In 1974, Ruiz and Prose interviewed applicants for a clerical position to assist. Alice Lang (1914-2004) had no background in similar services, but she was hired. She proved to be an angel. She enthusiastically found ways to make the service efficient and as helpful as possible. She found ways to keep poison dangers before the public. She sought expert advice from botanists and authored a popular book on plant poisoning. The UM College of Pharmacy saw the new PCC as a good resource for pharmacy graduates. Dr. Ed Krenzelok worked with Lang, EM, and the College to make the PCC among the best in the country. Enough trained staff were brought on-board to provide 24 hour coverage. Dr. Louis Ling, EM staff physician with an interest and expertise in toxicology replaced Krenzelok when he became Director of the Pittsburg Childrenʼs Hospital Poison Center in 1984. The Poison Control Center continues as a state-wide public treasure.

Hyperbaric Medicine came to HCGH in 1964. Hitchcock had read articles written by Professor of Surgery Ite Boerema at the University of Amsterdam, Holland, regarding the successful treatment of gas gangrene infections by administering oxygen to afflicted patients in a high pressure chamber. Gas gangrene results from Clostridium infections. Clostridium bacteria are anaerobes that cannot survive in tissue that is

well oxygenated. This form of infection had a very high mortality rate and was not uncommon in post surgical patients and in trauma patients. Hitchcock used his genius for obtaining financial support to receive a National Institutes of Health grant for a state-of-the-art multi-place hyperbaric chamber and its supporting research facility located on the same block as the old General. A large contribution from a private benefactor also helped make it possible. The first patient was treated in 1964. HCGH became the Hyperbaric Oxygenation (HBO) center for the middle of the U.S. Many lives have been saved as a result. Some of the hoped-for benefits of hyperbaric oxygenation for certain conditions of hypoxia did not pass scientific study. Myocardial ischemia did not respond. However, HBO has remained life-saving in the treatment of severe bends, carbon monoxide poisoning, air embolism, and anaerobe infections. It is also beneficial for several forms of poor healing resulting from poor tissue oxygenation. Because many cases presented as emergencies, it was natural that EM would assume responsibility for the HBO service when the two surgeons most involved in hyperbaric medicine, Hitchcock and Dr. John Haglin (1920-2001), Assistant Chief of Surgery, retired. Surgery and other departments have access to the HBO facility through EM. Cheryl Adkinson, MD, an emergency physician also board certified in Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine (UHM), is Director of Hyperbaric Medicine. She directs the HBO Facility and its certified UHM nursing and engineering personnel. She is assisted by Robert Collier, MD and Eric Gross, MD, also EM staff physicians boarded in UHM. EM has been pleased to collaborate with Dr. Gaylan Rockswold, Chief of Neurosurgery, and other surgeons in exploring the uses of HBO.

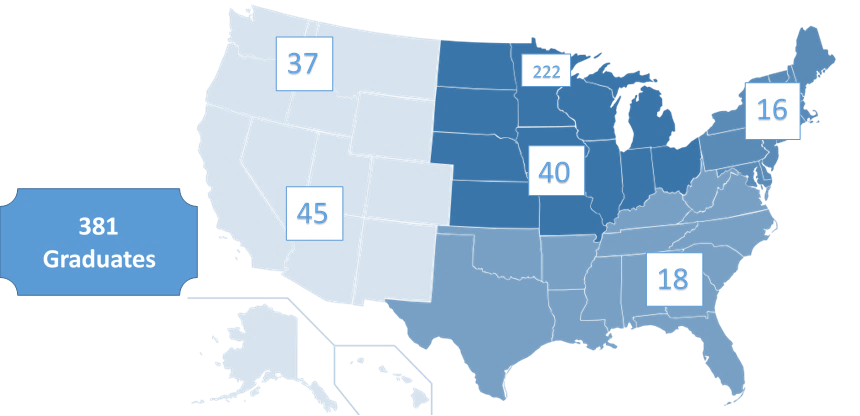

Thirty-seven years after its beginning, over 300 EM physicians have graduated from the HCMC residency. Many are practicing in Minnesota. Many have provided service to their communities and to the specialty. Many have reached the academic level of Professor of Emergency Medicine. Hildred Prose RN, the intrepid ED Nursing Director who instigated so much progress retired from her clinical duties in 1965 and became determined to preserve the history of “the General.” The move to the new hospital in 1976 could have meant a disastrous loss of historic documents and equipment were it not for Prose. She convinced hospital administration, with support from the HCMC Service League, to devote a few rooms in the basement of the new hospital to house a collection of documents, photos, equipment, and written histories of experiences she and others had saved. This formally became the HCMC Historical Museum in 1994. Audrey Kuhne and Donna Hoover, RN, Medicine Service Supervisor, among many others, helped Prose upgrade and maintain the exhibits in the museum. Prose fully retired in 2008 after 60 years of service. The museum is now open to the public.

by Ernest Ruiz, MD, FACEP (1931-2020)